Written by Lucy Rycroft-Smith

A research talk by any other name might an audience deplete

How do you decide which sessions to go to at a conference?

Two methods commonly employed are to look at session titles, and the names of those presenting (indeed, this may be all you have to go on).

Some twenty-five years ago, Salager-Meyer (1991) argued that because of the ballooning number of scientific research papers being published,

‘scientists would have to rely more and more on abstracts as a short, concise, complete and accurate source of information. Scientific paper abstracts are indeed a time-saving device that helps readers to decide whether the whole article is worth reading or not. Today, because of the hyperproduction of professional literature which is estimated to double every 12 years (Stix 1994), most scientists are content with reading the title only of the papers they deem interesting for their research purposes.’

There is some evidence that people use titles of papers alone to make decisions, for example in medicine eg (Goodman, 2000). They certainly use them to decide if the paper or session warrants further attention, hence ‘a title should indicate the topic and scope of the study, and be self-explanatory to readers in a given discipline’ (Salager-Meyer & Alcaraz Ariza, 2013). Moattarian & Alibabaee (2015) argue that ‘A title creates identity for any academic piece of work. The better a title is, the more easily readers can decide to read something.’ Writing good titles is a ‘challenging exercise’ and yet ‘no agreement seems to have been found on the standard and good title writing practice in different scientific disciplines and genres’ (Soler, 2007).

How do you decide on your research paper and talk titles? Is there a difference?

Have you ever been to a research talk or workshop where the reality seemed mismatched with the title?

Do you notice particularly beautiful, funny or stylish titles?

————————————————————————————————————————-

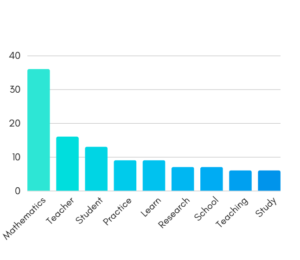

Taking a brief look at the session titles presented for the November 2018 BSRLM, we can perform some quick analysis. Of the 53 on offer, 38% (20) began with a verb, all of which were in present participle format (developing/designing/examining). Even this count is problematic, as verbs can behave like nouns when they are gerunds (failing GCSE mathematics) or adjectives (differing perspectives on…). 42%(22) began with a noun or an article before a noun (competencies/students/an exploration). A further two began with adjectives (differentiated/visible). The wordcloud above and chart below shows the relative frequency of words in the title:

All this is really no help, though, is it? Do you really choose your session based on the first word? Similarly, the two diagrams above probably don’t differ much from any conference on mathematics education. If you had the data set for the titles AND abstracts before the conference (which, in principle, every attendee did) – and assuming you had some time on your hands – how might you analyse it to help determine which sessions to attend?

Use of particular key words that are of research interest?

Readability of text? (Are you more attracted to a pithy abstract or a periphrastic one?)

Niche-ness of area? (Do you think an esoteric abstract means a quieter or more focused session?)

Humour, use of puns, or quotes?

—————————————————————————————————————————

One particular difficulty seems to be the possibility of disparity between the reality of the talk versus the title. In my experience, the more ‘academic’, the conference, the more variance here. On occasion, I have been in a session wishing desperately that I could leave – not because the talk is terrible, but because it simply wasn’t what I thought it would be.

Do we stop and evaluate this? Do we incentivise certain types of title; do we gatekeep; do we encourage a self-perpetuating status quo because the experts and authorities in the field do it a certain way and newcomers emulate? At the end of a conference, should we specifically ask attendees to rate closeness of fit between titles of sessions and what they delivered? And should we be asking those offering sessions to provide further information to help those attending choose between them, such as the type of research (design-based, case study, action research, theoretical, empirical etc), the potential scope and scale, the intended audience? Or would this reduce the cases of ‘serendipitous happenings’ at conferences, where you wander into a session almost by accident and it happens to spark something amazing in your professional life?

Lucy Rycroft-Smith

Cambridge Mathematics

References

Goodman, N. W. (2000). Survey of active verbs in the titles of clinical trial reports. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 320(7239), 914–915.

Moattarian, A., & Alibabaee, A. (2015). Syntactic Structures in Research Article Titles from Three Different Disciplines: Applied Linguistics, Civil Engineering, and Dentistry. Teaching Language Skills, 21(7), 27–50.

Salager‐Meyer, F. (1991). Medical English abstracts: How well are they structured? Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(7), 528–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199108)42:7<528::AID-ASI7>3.0.CO;2-2

Salager-Meyer, F., & Alcaraz Ariza, M. Á. (2013). Titles are “serious stuff”: a historical study of academic titles. JAHR, 4(1), 257–271.

Soler, V. (2007). Writing titles in science: An exploratory study. English for Specific Purposes, 26(1), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.08.001